Ig Credit: Fieldnotesbyfi

ig credit: fieldnotesbyfi

More Posts from Mcborow and Others

photos of dachas by Fyodor Savintev, published in Dacha: The Soviet Country Cottage (2023)

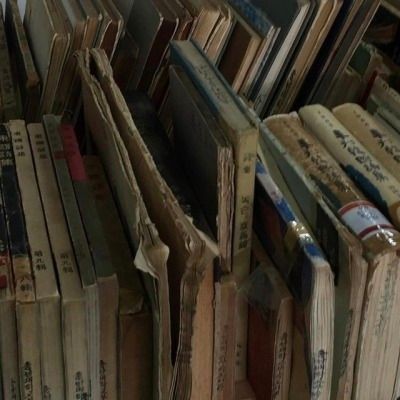

There is a musk that comes from academia, which I'll attempt to describe.

It starts with the smell of wood. Where a building isn't stone, it is old lacquered hard wood that has also been absorbing the elements for centuries. Outdoors, it is wet and slick, but indoors, the dryness preserves it, and absorbs the scents brought in such as leather and cigarettes and cigars and the spilled whiskey.

There is the scent of people as well, permeating throughout. Academia is often thought of as a solitary environment, but lectures and classes and clubs and parties, they bring together women, men and others in a tight space often. There's the scent of sweat and perfume and cologne, but also the inimitable aroma that comes from worn leather and damp wool. Breath these in deep enough, and your mind and soul are transported to events that have transpired over the course of decades, if not longer. The deep bellied laughter, the intimate whispers, and even the silence between two or more forbidden lovers, gazing from across the room.

Finally of course, there's the musk of books. Of paper, flax, cotton and leather, of the glue binding in the spine, and the collected dust of a hundred years. That scent is the book dying, the materials with which it was made slowly degrading over a prolonged period. A finely trained nose might even determine a book's age, from the distinct smell of the materials used by printers at the time.

Breath it all in, and let yourself feel everything that these fragrances evoke in your mind. Longing, desire, nostalgia, lust, anger, sadness, melancholy. The history that has passed may guide your present and future.

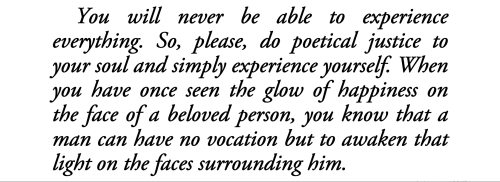

― Albert Camus, Notebooks: 1935-1951

- Sylvia Plath, from 'Ariel'

Photo by Kristina Delp on Unsplash

🍃🍂🍃

One uncanny aspect of translating is when I am grappling with a sentence that would sound particularly wrong if I tried to preserve any part of the original structure or idioms, because nothing about it matches the way one would phrase such an idea in my language, so what I need to do is mentally divorce the sentence from its syntax and vocabulary, to try and find how my language would give form to the same concepts. It always makes me wonder, what am I working with here? What is left when you remove the grammar and specific word choices from a sentence? I don’t know, a shapeless mental porridge of pure meaning, a nebulous feeling of what another brain has tried to express. I find it amazing that your mind knows just what to do with something so unfathomable—that it’s just like “right, right, give me a minute” as it distillates meaning out of words like it’s nothing then lassoes it down from the platonic realm of forms to give it a completely new shape. What is ‘meaning’ and how does it exist in your mind in this liminal moment after you’ve extracted it from a foreign language but haven’t yet found words in your own language that can embody it? I don’t know.

-

jesusperezarte liked this · 2 months ago

jesusperezarte liked this · 2 months ago -

enchantedescapade reblogged this · 2 months ago

enchantedescapade reblogged this · 2 months ago -

devilbooks reblogged this · 2 months ago

devilbooks reblogged this · 2 months ago -

the-woods-call-me reblogged this · 3 months ago

the-woods-call-me reblogged this · 3 months ago -

diewithasmile-e reblogged this · 3 months ago

diewithasmile-e reblogged this · 3 months ago -

diewithasmile-e liked this · 3 months ago

diewithasmile-e liked this · 3 months ago -

purplepalacecookiesalad liked this · 3 months ago

purplepalacecookiesalad liked this · 3 months ago -

innocuous-to-self reblogged this · 3 months ago

innocuous-to-self reblogged this · 3 months ago -

ilovebeeshoney liked this · 3 months ago

ilovebeeshoney liked this · 3 months ago -

alwayshalloweeninmyhead liked this · 4 months ago

alwayshalloweeninmyhead liked this · 4 months ago -

janespartan liked this · 4 months ago

janespartan liked this · 4 months ago -

study-hard-be-gay reblogged this · 4 months ago

study-hard-be-gay reblogged this · 4 months ago -

shakespeareanqueer liked this · 4 months ago

shakespeareanqueer liked this · 4 months ago -

girlslikegirlsandbooks reblogged this · 4 months ago

girlslikegirlsandbooks reblogged this · 4 months ago -

butterfly-sunshine-summer liked this · 4 months ago

butterfly-sunshine-summer liked this · 4 months ago -

myvirtualbookshelf reblogged this · 4 months ago

myvirtualbookshelf reblogged this · 4 months ago -

leonorthoughts reblogged this · 4 months ago

leonorthoughts reblogged this · 4 months ago -

invisible-disaster reblogged this · 5 months ago

invisible-disaster reblogged this · 5 months ago -

aestheticallypleasingpaper reblogged this · 5 months ago

aestheticallypleasingpaper reblogged this · 5 months ago -

hellhate liked this · 5 months ago

hellhate liked this · 5 months ago -

slowsweetlove reblogged this · 5 months ago

slowsweetlove reblogged this · 5 months ago -

dreamymeadow liked this · 5 months ago

dreamymeadow liked this · 5 months ago -

waggermama liked this · 5 months ago

waggermama liked this · 5 months ago -

lonelyapothecary reblogged this · 5 months ago

lonelyapothecary reblogged this · 5 months ago -

sherlieh reblogged this · 5 months ago

sherlieh reblogged this · 5 months ago -

elenaalouette liked this · 5 months ago

elenaalouette liked this · 5 months ago -

creepywonderland-pony liked this · 5 months ago

creepywonderland-pony liked this · 5 months ago -

lisgoe reblogged this · 5 months ago

lisgoe reblogged this · 5 months ago -

octoberg reblogged this · 5 months ago

octoberg reblogged this · 5 months ago -

shadowpirate reblogged this · 5 months ago

shadowpirate reblogged this · 5 months ago -

saladlovesyou liked this · 5 months ago

saladlovesyou liked this · 5 months ago -

shadowpirate reblogged this · 5 months ago

shadowpirate reblogged this · 5 months ago -

alifemeasuredincoffeespoons reblogged this · 5 months ago

alifemeasuredincoffeespoons reblogged this · 5 months ago -

acciobooksandsunshine reblogged this · 5 months ago

acciobooksandsunshine reblogged this · 5 months ago -

becomethebooks reblogged this · 5 months ago

becomethebooks reblogged this · 5 months ago -

traditionalgovernance liked this · 6 months ago

traditionalgovernance liked this · 6 months ago -

learningthroughdreaming reblogged this · 6 months ago

learningthroughdreaming reblogged this · 6 months ago -

revesdebosch liked this · 6 months ago

revesdebosch liked this · 6 months ago -

magicaloxford liked this · 6 months ago

magicaloxford liked this · 6 months ago -

aelstudies reblogged this · 6 months ago

aelstudies reblogged this · 6 months ago -

oftheoscarwildesortt reblogged this · 6 months ago

oftheoscarwildesortt reblogged this · 6 months ago -

i-am-mrsreckless reblogged this · 6 months ago

i-am-mrsreckless reblogged this · 6 months ago -

oftheoscarwildesortt liked this · 6 months ago

oftheoscarwildesortt liked this · 6 months ago -

iamnotswarley reblogged this · 6 months ago

iamnotswarley reblogged this · 6 months ago -

m-a-es-blog reblogged this · 6 months ago

m-a-es-blog reblogged this · 6 months ago -

roseharlaws liked this · 6 months ago

roseharlaws liked this · 6 months ago -

shewaswitthmedude liked this · 6 months ago

shewaswitthmedude liked this · 6 months ago -

lauraqueirozfr-blog liked this · 6 months ago

lauraqueirozfr-blog liked this · 6 months ago